At the turn of the century Danny Boyle was thinking about Kenneth Noye, the Brink’s-Mat gold bullion crook who evaded police in the 1980s. The coppers had dug up his garden and followed him to Spain, but couldn’t pin him down. Then, in 1996, a young man called Stephen Cameron ran Noye off a slip road on the M25 and Noye flipped, stabbing him to death. He was finally jailed in 2000 — becoming the inspiration for Boyle’s seminal 2002 zombie movie, 28 Days Later.

“Our idea came from road rage,” the director says. A visceral Alex Garland script about a “rage virus” transmitted from test lab chimps to humans showed a Britain that had been wiped out, and fast. “Because we are all capable of rage, no matter what you’ve got at stake.”

They were shooting when two planes flew into the World Trade Center. Suddenly, road rage was not all over the front pages but replaced by the war on terror, a deeper paranoia that felt reflected in a film about millions living in fear. 28 Days Later was a huge hit, making nearly £57 millionfrom a budget of about £5 million.

• Read more film reviews, guides about what to watch and interviews

Crucial to its success was an indelible early scene, in which Cillian Murphy wakes from a coma and staggers from hospital into a deserted London. “It evoked this sense that cities were vulnerable,” Boyle says, explaining why his film resonated post-9/11. “You think they are almighty, but suddenly cities felt fearful. And that happened again during Covid.”

In 2020, as the lockdowns took hold, people shared that eerie clip again: a man in scrubs wandering bewildered across Westminster Bridge. The 2007 sequel, 28 Weeks Later, featuring quarantines and cures, was similarly resonant.

Now Boyle is back for more with 28 Years Later, in which Isla (Jodie Comer) and Jamie (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) live on a virus-free island just off the British mainland, connected by a tidal causeway. Their 12-year-old son sees a distant fire and feels there may be more to the mainland than his parents have led him to believe. The film depicts Britain as an isolated, crippled rock devoid of decent human life and populated only by the deranged — but more on Brexit later.

I meet Boyle bright and early in London, not long after a dawn cover shoot on Westminster Bridge to recreate that memorable opening scene. “Oh, it’s beautiful, the city’s asleep,” he smiles. He mentions Wordsworth’s sonnet, Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802, and is remarkably chipper for a man who has been up since 4am. But then chipper is what the 68-year-old director of Trainspotting is. From his Oscar for Slumdog Millionaire in 2009 to his bold London Olympics opening ceremony featuring Daniel Craig’s 007 and the Queen, he is one of life’s great enthusiasts, a man who could find joy in descaling the coffee machine.

I ask if it was hard to pull off a deserted London in 28 Days Later. “No,” he says, surprisingly. “We didn’t have the money to close the bridge, but had a plan to be there at 4am. The police can’t ask the traffic to stop, but they will allow you to ask drivers. So we hired a lot of girls, including my own daughter, who was 18. Anybody driving at that time is a bloke, so we had the girls lean in, saying, ‘Do you mind?’ And it worked fine.”

The end of 28 Weeks Later showed the virus reaching Paris, but the opening text of Boyle’s new film makes it clear that “rage” has since been shoved back across the Channel. “This is a very, very British film,” Boyle says. “It’s not a political film, but when we started work on this, it came after Brexit and that retrenchment to older values, and you cannot help but think that this film is a response to that. The film is full of British actors, and our obsessions.”

It has also been conceived as the first in a new trilogy, with a second film, 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple, due in January. A third script is “ready and waiting” for finance, “which will be dictated by how well this one does,” Boyle says, laughing. “You have to wait until the public declare their enthusiasm or not. And I cannot imagine what the Americans are going to make of it. Obviously you’d love it to be a hit there, because they’ve given us the money, but really? We’ve made the film for here, my homeland.”

Danny Boyle recreates a scene from 28 Days Later with Cillian Murphy, below

TOM BARNES FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES CULTURE

Boyle was born in 1956 in Radcliffe, Greater Manchester, one of three children to his Irish Catholic parents, Frank and Annie. He was an altar boy and, until his teens, looked destined for the priesthood. Instead he edged towards theatre, directing for the Royal Court and the RSC before 1994’s black comedy Shallow Grave launched his and Ewan McGregor’s film careers. Two years later Trainspotting made the pair stars.

Boyle turns 70 next year. Has time changed his relationship with the faith of his youth? “Not in a conventional sense,” he says, “although I’m agnostic, really, and the older you get, the more you see things differently. I’m obsessed with the autonomic — those processes we have no control over, but are completely why we’re alive. Like breathing. If you had to remember to breathe, you’d be dead with the effort of it. But we have this system that runs it for us. What is this? There are mysteries we do not understand, and I’m open to those.”

Boyle does not so much answer questions as turn them into a platform for further questions. That curiosity seeps into all his films, often making them prescient. The chimps in 28 Days Later are infected by the rage virus after being bombarded with images of war and brutality on screen. Fast-forward 23 years to today, I say, and are we not all monkeys scrolling distressing images on our phones?

• The best films of 2025 so far

“Well, yes, we think we are so advanced, and becoming more sophisticated, but nothing in that footage is dated,” Boyle says. “There is this intolerance and you hope that goodness will return, and that we’ll start paying public servants better, cherishing teachers and doctors, those institutions we are improved by or that save us. They should be the people who inspire us, not the technologists, who feed us this stuff as a result of the devotion we show them.

“But you have to take personal responsibility,” he adds, on a roll, “to try and keep a spirit alive. There’s this great Embrace song called All You Good Good People, and I still have this belief in good. Progress isn’t based solely on technology, but on soul. My mother brought me up to believe that, and younger generations seem like they are actually better people than we were.” Boyle has three grown-up children with his ex-partner, the casting director Gail Stevens.

“All that work in education that people take the piss out of has worked,” he says. “It seems to me that young people are more understanding. My son’s a better man than I was, a more valuable member of society. A lot of that is due to the work his schools put in to raise a better human than us lot and, you know, I think I improved on my dad as well.”

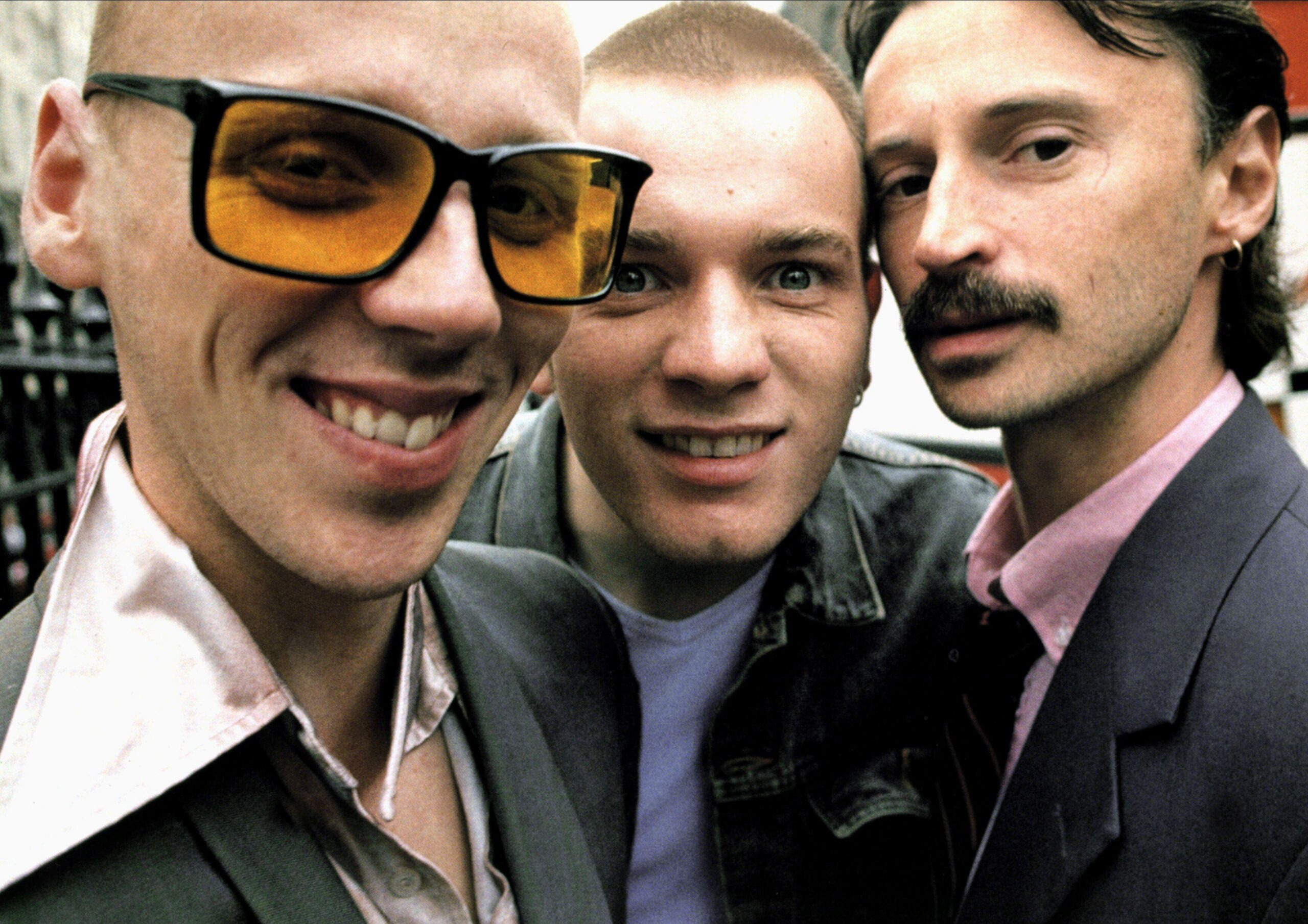

Ewen Bremner, Ewan McGregor and Robert Carlyle in Trainspotting

ALAMY

This optimism runs through Boyle’s back catalogue. Renton makes it out in Trainspotting. Jamal triumphs in Slumdog Millionaire. Aron flees the rock in 127 Hours — his 2010 film about a man trapped in a canyon — albeit without an arm. Boyle titled his Olympics ceremony Isles of Wonder, taking the UK’s past and present and making it all a vibrant part of who we are.

Thirteen years on from London 2012, is there anything he wishes he’d done differently? “Well, there was a lot of advice and warnings we ignored, but the one that we listened to that I regret deeply [meant] that we didn’t feature the BBC enough,” Boyle says. He would have liked to have included a segment celebrating the broadcaster, similar to his dancing NHS nurses. “Because I look now at news values and who to trust, and think, ‘F*** me — we should look after that.’

• 5 of the best survival movies

“It doesn’t matter whether you approve of it or not. It is just the idea of this national broadcaster with some kind of values you can rely on. These technology internationalists will have you believe that they don’t matter, that there’s something global much more important. But they do matter. They define us. But we were told we couldn’t feature them by the IOC [International Olympic Committee].”

Boyle’s stories keep coming. Of his failed attempt to direct the most recent James Bond film (Boyle left No Time to Die after two years in development, citing creative differences with Eon Productions), he says: “It was bound to end like that, but there is no cure for curiosity. We couldn’t find agreement.”

Freida Pinto in Slumdog Millionaire

ALAMY

Asked which of his films was the hardest to make, he quickly says Sunshine, a 2007 sci-fi thriller with Cillian Murphy. “Doing space movies? Would not recommend.” And of the underrated box-office bomb A Life Less Ordinary (1997), starring Cameron Diaz and McGregor, Boyle says with a cackle: “There’s a great saying: ‘If the people don’t want to come, nothing will stop them!’ But it was number one in Belgium for three weeks.”

I ask Boyle about Trump’s proposed film tariffs. “Who knows if it will stick or not? The film industry is extraordinarily international.” But rather than talk about the business, he is suddenly reminded of the dance performance he saw the night before, created by the French choreographers (La)Horde. His enthusiasm is a recommendation, but also a plea for funding and a neat summation of the director’s ethos: he is a profound believer in the power of the arts to tell myriad stories that will change and improve us.

“And people ask if we can prove that power,” he says. “Can we prove that to people who make decisions? Well, if you saw La(Horde), you just feel better. It was incredible. It made me a better person. I felt lifted, and it only cost 20 quid.” He beams. “Culture is good for us! It’s like blood transfusion, isn’t it?”

28 Years Later is in cinemas from Jun 20

Are you looking forward to 28 Years Later? Let us know in the comments below