The history of the dead – or, more precisely, the history of the living’s fascination with the dead – is an intriguing one.

As a researcher of the supernatural, I’m often pulled aside at conferences or at the school gate, and told in furtive whispers about people’s encounters with the dead.

The dead haunt our imagination in a number of different forms, whether as “cold spots”, or the walking dead popularised in zombie franchises such as 28 Days Later.

The franchise’s latest release, 28 Years Later, brings back the Hollywood zombie in all its glory – but these archetypal creatures have a much wider and varied history.

Zombis, revenants and the returning dead

A zombie is typically a reanimated corpse: a category of the returning dead. Scholars refer to them as “revenants”, and continue to argue over their exact characteristics.

In the Haitian Vodou religion, the zombi is not the same as the Hollywood zombie. Instead, zombi are people who, as a religious punishment, are drugged, buried alive, then dug out and forced into slavery.

The Hollywood zombie, however, draws more from medieval European stories about the returning dead than from Vodou.

A perfect setting for a ‘zombie’ film

In 28 Years Later, the latest entry in Danny Boyle’s blockbuster horror franchise, the monsters technically aren’t zombies because they aren’t dead. Instead, they are infected by a “rage virus”, accidentally released by a group of animal rights activists in the beginning of the first film.

This third film focuses on events almost three decades after the first film. The British Isles is quarantined, and the young protagonist Spike (Alfie Williams) and his family live in a village on Lindisfarne Island. This island, one of the most important sites in early medieval British Christianity, is isolated and protected by a tidal causeway that links it to the mainland.

Sony Pictures

The film leans heavily on how we imagine the medieval world, with scenes showing silhouetted fletchers at work making arrows, children training with bows, towering ossuaries and various memento mori. There’s also footage from earlier depictions of medieval warfare. And at one point, the characters seek sanctuary in the ruins of Fountains Abbey, in Yorkshire, which was built in 1132.

The medieval locations and imagery of 28 Years Later evoke the long history of revenants, and the returned dead who once roved medieval England.

Early accounts of the medieval dead

In the medieval world, or at least the parts that wrote in Latin, the returning dead were usually called spiritus (“spirit”), but they weren’t limited to the non-corporeal like today’s ghosts are.

Medieval Latin Christians from as early as the 3rd century saw the dead as part of a parallel society that mirrored the world of the living, where each group relied on the other to aid them through the afterlife.

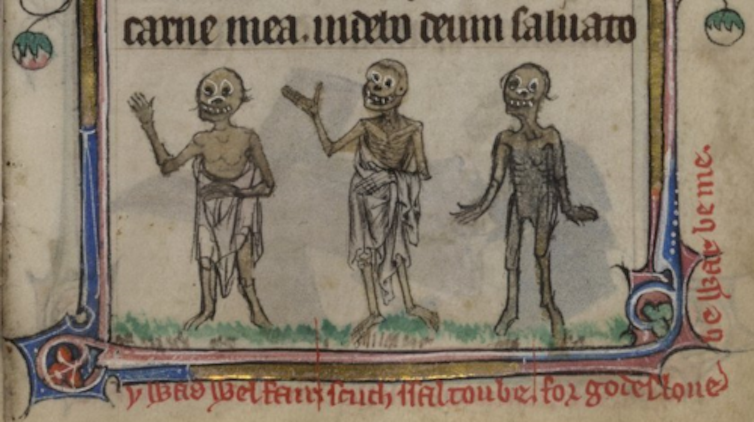

British Library, Yates Thompson MS 13

While some medieval ghosts would warn the living about what awaited sinners in the afterlife, or lead their relatives to treasure, or prophesise the future, some also returned to terrorise the living.

And like the “zombies” affected by the rage virus in 28 Years Later, these revenants could go into a frenzy in the presence of the living.

Thietmar, the Prince-Bishop of Merseburg, Germany, wrote the Chronicon Thietmari (Thietmar’s Chronicle) between 1012 and 1018, and included a number of ghost stories that featured revenants.

Although not all of them framed the dead as terrifying, they certainly didn’t paint them as friendly, either. In one story, a congregation of the dead at a church set the priest upon the altar, before burning him to ashes – intended to be read as a mirror of pagan sacrifice.

These dead were physical beings, capable of seizing a man and sacrificing him in his own church.

A threat to be dealt with

The English monastic historian William of Newburgh (1136–98) wrote revenants were so common in his day that recording them all would be exhausting. According to him, the returned dead were frequently seen in 12th century England.

So, instead of providing a exhausting list, he offered some choice examples which, like most medieval ghost stories, had a good Christian moral attached to them.

William’s revenants mostly killed the people of the towns they lived, returning to the grave between their escapades. But the medieval English had a method for dealing with these monsters; they dug them up, tore out the heart and then burned the body.

Other revenants were dealt with less harshly, William explained. In one case, all it took was the Bishop of Lincoln writing a letter of absolution to stop a dead man returning to his widow’s bed.

These medieval dead were also thought to spread disease – much like those infected with the rage virus – and were capable of physically killing someone.

British Library, Arundel MS 83.

The undead, further north

In medieval Scandinavia and Iceland, the undead draugr were extremely strong, hideous to look at and stunk of decomposition. Some were immune to human weapons and often killed animals near their tombs before building up to kill humans. Like their English counterparts, they also spread disease.

But according to the Eyrbyggja saga, an anonymous 13th or 14th century text written in Iceland, all it took was a type of community court and the threat of legal action to drive off these returned dead.

It’s a method the survivors in 28 Years Later didn’t try.

The dead live on

The first-hand zombie stories that were common during the medieval period started to dwindle in the 16th century with the Protestant Reformation, which focused more on individuals’ behaviours and salvation.

Nonetheless, their influence can still be felt in Catholic ritual practices today, such as in prayers offered for the dead, and the lighting of votive candles.

We still tell ghost stories, and we still worry about things that go bump in the night. And of course, we continue to explore the undead in all its forms on the big screen.