After the end

What “The Last of Us” teaches us about society, survival, systems, and self

“The Last of Us” started as a video game developed by Naughty Dog, morphed into a popular 2023 HBO series, and is that rare cultural sensation poised to gain in popularity when the second season drops on April 13.

The series depicts a deadly fungal pandemic that has obliterated much of the United States, leaving a smuggler named Joel and a teenage girl named Ellie to journey across the country, warding off zombie-like humans, eluding an oppressive government regime, and outwitting roving bands of marauders.

It’s bloody. It’s bleak. And we love it. Every dark moment.

But why?

Members of our faculty — from a fungus expert to teachers of dystopian film, games, and books — unravel the meaning and the madness behind our ongoing fascination with post-apocalyptic narratives.

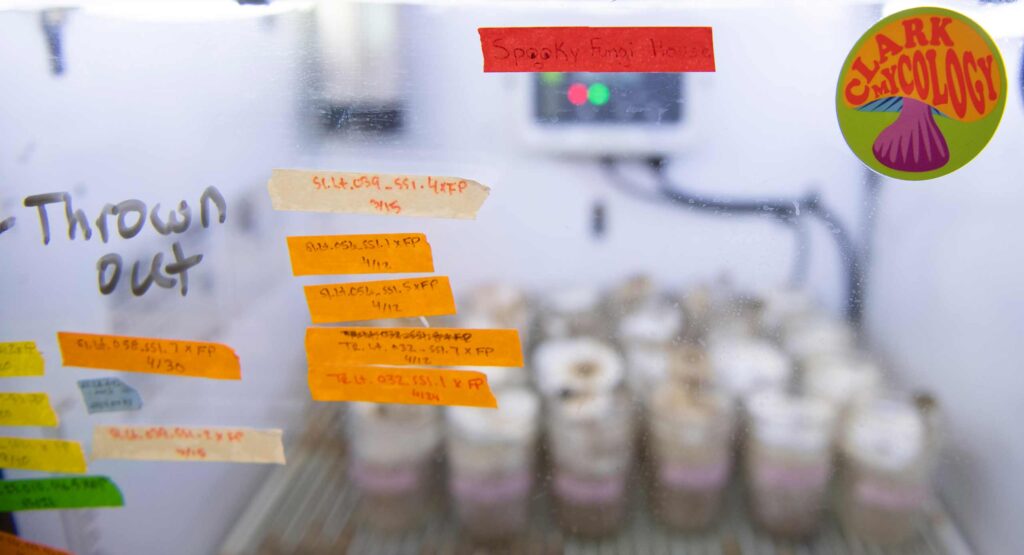

Above: Mycelium isolate, Basidiobolus ranarum is an opportunistic pathogen which lives in the gastrointestinal tract of amphibians. Lauren Parry, a Ph.D. student working in the Tabima Lab studies antifungal response trends for Basidiobolus using type, lab grown isolates, and isolates under selective pressures in the urbanized Worcester watershed. The time lapse was created from photos taken every five minutes for six days–a total of 1,676 separate photos.

Why do we revel in tales of our own destruction? Are there life-affirming lessons in the wake of mass catastrophe? And are we confident that if the fateful day arrives when our planet shudders, the last of us will include — us?

Let’s find out …

Part 1. Why are we drawn to apocalyptic narratives?

How we embrace, and grapple with, dystopian storytelling

Betsy Huang, an English professor with an affinity for speculative fiction, recently rewatched season one of “The Last of Us” in preparation for the season two premiere. Season two is dropping at a time when many people are examining the roles of institutions in their lives, Huang says, a concept depicted in the show and video game, and a common theme of post-apocalyptic stories in general.

“I think that ‘The Last of Us’ in the current moment is reminding us of the frailty of all of our institutions, whether it’s our government or educational institutions,” she says. “One can imagine that if all of these institutions disappeared, we’d want them back because we’d all of a sudden realize it is difficult to live without a lot of them.”

What worries Huang, however, is that the show could encourage a sense of radical individualism in its viewers. One interpretation of the story could be to save the one person you can and “screw everybody else,” she says.

To Huang, “The Last of Us” is a familiar post-apocalyptic tale, with similarities to Octavia Butler’s “Parable of the Sower” and other road narratives, and the show has echoes of “The Walking Dead.” What drives people’s interest in works of science fiction evolves over time, Huang says, but the main appeal is the sense of loss and hopelessness portrayed in these stories.

“Post-apocalyptic stories are about loss on a mass scale — it’s about the rest of humanity or an institution or an organization or a social structure that you count on so much that it gives you a sense of purpose without you even realizing it on a conscious level.”

“Everyone knows what loss means and it’s the scale of that loss that I think a lot of these works of fiction address very well,” she says. “For the most part, post-apocalyptic stories are about loss on a mass scale — it’s about the rest of humanity or an institution or an organization or a social structure that you count on so much that it gives you a sense of purpose without you even realizing it on a conscious level.

“Once that is taken away,” she continues, “what remains in everything that you have counted on to carry you through the day?”

When works in this genre explore restoring social order and reestablishing institutions, the result is often repressive.

“They’re almost always overreaching, almost always authoritarian, and perhaps even worse,” Huang says. “It becomes an evaluation of whose lives matter and whose lives perhaps don’t. That becomes an opportunity for interrogating what living a meaningful life means.”

It’s a cliché, Huang says, that speculative fiction is a critique of the present and a reflection of the past. What this morbid fascination suggests, she believes, is that people don’t have a happy outlook for the future.

“I think, to many of us, the future is always already dystopian, always already filled with death and destruction, always already asking us to think about sacrifices that we have to make, always already critiquing us and criticizing us for the excesses and the extravagances and perhaps the kinds of problematic, wasteful, and destructive behaviors that we engage in,” she says.

Part 2. How do the games we play reflect our times?

A gamer’s guide to the chaotic and the cozy

When gamers describe playing “The Last of Us,” many speak about their emotional connection to the post-apocalyptic story and its lead characters Joel and Ellie.

“I never played a game before with so much emotion,” one gamer writes in a review. “I cried at least four to five times through it, and it takes a lot for me to cry.”

It’s a typical response to the 2013 PlayStation game, which drew much critical acclaim, winning the DICE Awards’ Game of the Year, the equivalent of a Best Picture Oscar. And it’s a reaction that Ulm, professor of practice in Clark’s Becker School of Design & Technology, has observed throughout her decades of playing and creating games.

“Our experience of playing a game isn’t just about the language we use to express our feelings and our thoughts — it’s also this visceral response, because when we’re playing a game, it’s a physical interaction,” Ulm says, “It’s a chemical response, whether we’re happy or sad or scared.”

Gamers first embraced “The Last of Us” because of its “really exciting world-building and the ability to embody the characters and play as Joel or Ellie, which brought about a deep connection and expression of how this reflected ourselves,” she explains.

“Games provide that safe space to explore dangerous or scary topics. And often that’s going to be something about our society.”

Yet, once the story migrated to HBO, it became even more culturally significant because of recent real-world “pivotal events,” including a global pandemic.

People are drawn to “The Last of Us” and other post-apocalyptic games because their stories feel chillingly familiar, Ulm says. “Games provide that safe space to explore dangerous or scary topics, and often that’s going to be something about our society.”

In “The Last of Us,” a “zombie” fungus overtakes humans, driving them to hunt and infect others. Since the release of “Zombie, Zombie” in 1984, electronic games have tapped into the age-old stories of will-less, speechless, but physically powerful beings.

Post-apocalyptic zombie games tap into some of our most deeply held fears about our humanity, forcing us to consider “what is really at our core,” according to Ulm.

“What would it mean to lose control or not actually have a purpose or autonomy — in this case, a brainlessness? What does it mean to be on autopilot?” We face our existential anxieties “about whether we’re going to find something meaningful or not, or if it’s just an instinctual, brainless creature we could become.”

There is an alternative to such fiery, chaotic games, however. “Cozy games,” she says, offer “something positive, something with a human core, and I think that’s a story worth telling as well.”

With their calm, community-oriented experiences, cozy games became popular during the pandemic, when players flocked to “Animal Crossing.” Some games, like “I Am Future: Cozy Apocalypse Survival,” even combine the cozy and post-apocalyptic genres.

Part 3. What is science and what is fiction?

Don’t fear the fungus — but watch your step

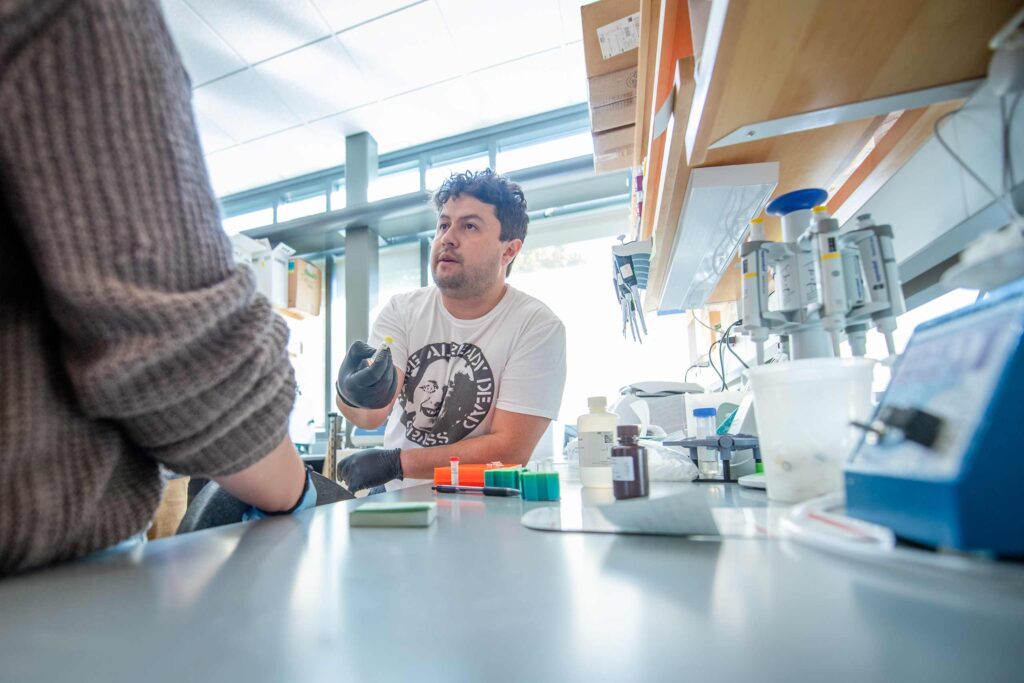

Biology professor and mycologist Javier Tabima Restrepo plays a lot of video games — before he became a parent, it was probably his biggest hobby after playing soccer — and “The Last of Us” is among them. The video game and HBO adaptation starring Pedro Pascal, who happens to be one of Tabima’s favorite actors, spins a fictional tale about the kinds of organisms Tabima researches every day.

“From a psychological perspective, they clearly are trying to sell an idea that’s a little bit absurd,” Tabima says of the depiction of cordyceps, a genus of parasitic fungi, which, in the game and show, cause an infection that obliterates mankind. Though these kinds of parasitic fungi can infect and kill insects in real life, they don’t reanimate corpses, Tabima stresses, something fellow Clark mycologist and biology Professor David Hibbett has emphasized.

The video game and show’s artistic rendition of cordyceps, while stunning, is imperfect, Tabima insists, and more closely resembles chicken of the woods, a yellow-orange edible mushroom. Cordyceps often appear as cylindrical-shaped fungi that grow off the body of insects such as ants. Tabima has collected these specimens firsthand while working with researcher Tatiana I. Sanjuan in Colombia. In a 2015 paper published in Fungal Biology, their team described five new species of the genome. The project tapped into Tabima’s passion for understanding the molecular process of differentiation between species and populations.

Cordyceps, the fungus depicted in “The Last of Us,” appear as cylindrical-shaped fungi that grow off the body of ants. This carpenter ant is from the lab of Biology Professor, Kaitlyn Mathis, who studies the complex web of interactions between insects species that provide ecosystem services, like pest control, in agroecosystems. The image was created by stacking and blending 20 separate photos.

What really excites Tabima is that “The Last of Us” arrives on television screens amid a blooming interest in fungi spurred by pop culture, a desire to connect with nature, a fascination with creative cooking.

“It’s fantastic because the more that we can get the voice out that fungi are cool, the better,” says Tabima. Mushrooms have gone mainstream with the help of books like “Entangled Life” by biologist Merlin Sheldrake and even the little red mushroom from Nintendo’s Super Mario. They appear on people’s dinner plates much more frequently than they did a few decades ago — in 2022, mushrooms were named the ingredient of the year by the New York Times.

“Fungi give us food. Fungi give plants the ability to be able to collect resources from the soil. Fungi are decomposers that allow nutrient cycling. Fungi provide us with antibiotics. Without fungi, we’ve got nothing.”

As different kinds of media stoke mushroom mania, Tabima wants to ensure the public doesn’t miss out on important emerging fungal research. He researches the genus Basidiobolus, including whether it could become a more prevalent human pathogen. In his lab, students examine Basidiobolus found in the gut biome of frogs. But, with amphibian populations declining because of habitat loss, and with Basidiobolus already able to infect vertebrates, Tabima and students want to understand whether humans are at risk of being infected and whether Basidiobolus can resist antifungal treatments.

Meanwhile, some experts believe the next pandemic could be fungal, Tabima notes. “That’s something that we need to be very aware of,” he says, quickly adding that the risk shouldn’t cause mycophobia. Tabima believes that the infection depicted in “The Last of Us” is unlikely to ever occur. “Mammals have existed on earth for a very long time and so have fungi,” he says. “If that interaction could have occurred, it would have by now.”

At the end of the day, Tabima encourages viewers to enjoy “The Last of Us” at face value.

“Enjoy it because the writing is superb, the story is great, the actors are perfect. Don’t fall into fear of fungi,” he says. “Fungi are much more beneficial than detrimental. Fungi give us food. Fungi give plants the ability to be able to collect resources from the soil. Fungi are decomposers that allow nutrient cycling. Fungi provide us with antibiotics. Without fungi, we’ve got nothing.”

Part 4. Do you know your zombie apocalypse movies?

Rolling the world’s final credits

Movies have imagined the end of the world in so many ways, it’s almost impossible to keep track.

Sometimes the planet’s demise arrives in the form of a virus that turns the living into the living dead.

Or a nuclear war that leaves the irradiated survivors wandering a still-smoking landscape in search of any reason to keep breathing.

Or an invasion of body snatchers, or cyborg terminators, or Marvel supervillain Thanos snapping his galaxy-crushing fingers.

And other times it’s simply a matter of Charlton Heston dropping to his knees in the shadow of the severed Statue of Liberty and raging, “You maniacs! You blew it up! DAMN YOU!” (If only he’d listened to the apes, who’d been trying to tell him exactly that.)

Hugh Manon, associate professor and chair of the Department of Visual and Performing Arts, has a particular fondness for a good post-apocalypse movie (and, admittedly, some bad ones). “The Last of Us” premise of a lone man transports a teenage girl across a ravaged landscape strikes a familiar chord with the film scholar, who teaches George Romero’s 1968 zombie classic “Night of the Living Dead” as a foundational entry in the horror canon.

“If enough zombies bite enough people, the world becomes all zombies, and the people are gone. We understand the logic that the Earth is going to reach a point where something dramatically inverts the way things are supposed to work. Something is going to subsume the human species.”

Apocalyptic movies, zombie-driven or otherwise, are an “essentially narcissistic” genre, Manon contends.

“They sort of invert what actually happens with human beings, which is that we die and the world lives on,” he says. “In these films, the world dies and humans live on. It’s counterintuitive because post-apocalypse movies seem to be taking humans out of the picture when they actually make human beings even more central to the picture.

“People today talk about how culture has taken a swing in the direction of pathological narcissism. Maybe a marker of that is the fact that apocalypse narratives are more popular today than they’ve ever been.”

“The Last of Us” follows Manon’s rule of thumb for a true post-apocalypse movie: The action has to range beyond a single location, reflecting the planetary impact of the disaster. Narrower-focused films like John Carpenter’s claustrophobic masterpiece “The Thing” (1982), set at a remote Arctic outpost, feel almost pre-apocalyptic by comparison, presaging the devastation to come.

For an apocalyptic tale that will truly make you think, Manon recommends 2018’s “Annihilation,” starring Natalie Portman as a scientist investigating a so-called “disaster zone” where an alien presence has altered everything inside the ecosystem, from the life forms to the laws of physics. “It’s really interesting philosophically, and it’s also kind of gross and scary,” he says. “It’s fantastic.”

“I don’t think any scientist is denying the fact that at some point, something is going to wipe us out, whether it’s a meteor or a contagion, or if global warming gets to the point where it’s simply impossible to survive,” Manon says. “These films know that, and they want to thrill us with the fantasy that we’ll still be here. If anything, it’s a more life-engaged genre than most.”

Part 5. What is the connection between nature and culture?

Course examines humans’ tangled relationship with fungi

Before “The Last of Us,” we might not have equated fungi with killer zombies. Instead, over thousands of years, we have looked to fungi — usually in the form of mushrooms — for food, medicine, storytelling, and spiritualism.

There was The Iceman we now call Ötzi, discovered by hikers on the Austria-Italy border in 1991, who lived and died more than 5,000 years ago. Along with his copper axe, knife, arrows, and baskets, Ötzi carried two species of wood-decaying mushrooms.

And there was Fungus Man, accompanied by the trickster Raven, key characters in the Haida people’s creation story in the Pacific Northwest.

They are just two of the many examples that students encounter in Plants, People, and Fungi, an advanced course focused on humans’ age-old relationships with flora and funga. New to Clark this spring, the class is taught by mycologist David Hibbett, the Andrea B. and Peter D. Klein ’64 Distinguished Professor of Biology, and ethnobotanist Morgan Ruelle, associate professor in the Department of Sustainability and Social Justice.

“Our cultures and ways of knowing are really shaped by plants and how we use them for food, for health, for energy. There’s this mutual benefit in all these relationships that emerges strongly as we go through the course.”

“I’m having a tremendous amount of fun teaching the course,” says Hibbett, who joined Clark in 1999 and is now a world-renowned expert on the evolutionary biology of mushroom-forming fungi. “It’s plants and fungi. It’s basic botany and mycology. And it’s ethnobotany and ethnomycology. So it’s very interdisciplinary.”

Ruelle brings expertise on how Indigenous and other place-based ecological knowledge systems can be combined with scientific research to develop sustainable solutions.

“We can approach the study of human-plant-fungal relations from many different disciplinary perspectives, and I think that David and I are demonstrating that in each class,” says Ruelle, who met Hibbett after joining Clark in 2018.

Hibbett dives into the biochemical properties of plants and fungi, and their scientific and evolutionary history. An ongoing theme in the course has been humans’ “give and take” with plants and fungi, Ruelle says.

“We often describe it as co-evolutionary. It’s not only that we domesticate plants, but Michael Pollan has written that the plants also domesticate us,” he says. “We shape the plants genetically so that they better serve our needs, and sometimes they become dependent on us because we provide protection and promote their reproduction. On the other hand, our cultures and ways of knowing are really shaped by plants and how we use them for food, for health, for energy. There’s this mutual benefit in all these relationships that emerges strongly as we go through the course.”

Yet, Indigenous knowledge of plants and fungi also has been exploited, according to Hibbett. “Taxonomy is inextricably connected to the history of colonization because so much of what we know about plants, fungi, and animals outside of North America and Western Europe really blossomed during the 19th century,” he explains, “when you had naturalists going around the world collecting the riches of the planet and bringing them back to museums and botanical gardens and zoos in Europe, principally, and then later in North America.”

Story: Melissa Hanson, Jim Keogh, Meredith King

Photos: Steven King

Video: Beth Prendergast