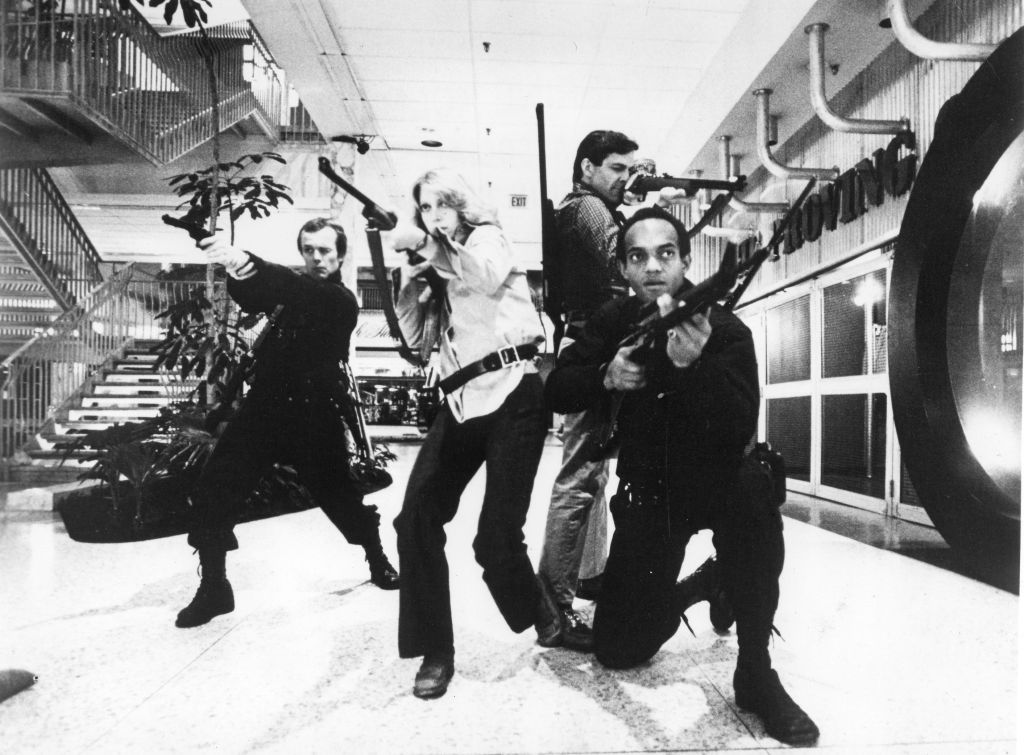

Gaylen Ross has only a handful of acting credits to her name, but the first of them remains significant enough even today for her to be permanently canonized in horror film history: “Dawn of the Dead.” Playing television producer Fran Parker for writer-director George A. Romero, Ross joins what’s otherwise a boys’ club cast to combat zombies (and post-apocalyptic boredom) in an abandoned shopping mall, in the process adding to the genre’s then-nascent collection of heroines who are forced to summon strength and resourcefulness in the face of unimaginable — and deadly — circumstances.

In the 45 years since the film’s release, Ross became an award-winning documentary filmmaker, trading Romero’s anti-consumerist metaphors for more literal explorations of social and historical causes with films like “Killing Kasztner” and “Beijing Spring.” Yet as she raises funds for her latest project, “Sapiro: The Jew Who Sued Ford,” “Dawn of the Dead’s” North American anniversary rekindles her connection to a phase of her career whose endurance the late Romero would no doubt appreciate: it refuses to die.

To commemorate that anniversary, “Dawn of the Dead” returns to theaters, including a handful of shows — including on May 24 at Los Angeles’ Orpheum Theatre — featuring a live performance of the film’s original score by Claudio Simonetti’s Goblin. Ross recently spoke to Variety to discuss her role in what has now become an indisputable classic of the genre, from her first memories of its visionary filmmaker to the mischief made in the Pennsylvania mall where it was mostly shot to the lasting impact it has made on her life.

Popular on Variety

Does it surprise you that “Dawn of the Dead” has been venerated as a masterpiece?

I think it’s quite incredible. I just did a Q&A for the 45th anniversary a few weeks ago, and you have children and grandchildren, these generations who respond to this film in a way that you would think that there would be a feeling of a film being dated, or the effects are not as sophisticated. But the way that audiences react to this film, it’s pretty amazing. George tapped into something that’s not just horror, but something else that made the film last this long, and this popular.

Was it something that you in any way immediately identified was different?

I actually took the role before I knew who George was, and after he cast, he did a screening of “Night of the Living Dead.” I was like, “this is going to be interesting.” I did remember saying, “what are we going to do about this woman character? I’m not going to scream and cry, and if that’s how we’re doing this, then I don’t feel comfortable doing it.” So it was an interesting dialogue that George and I had at the beginning about how are we going to make Fran not a victim, and part of the characters that were active? And it evolved… he rewrote it while we were working, because he also felt we needed to empower her more.

Dawn of the Dead/ Katherine Kolbert

Did George tend to be very practical as a director, or was he engaging you and the rest of the cast at all in discussions about its more sociological themes?

He was a very gentle director, and he didn’t speak much, but he would let you know what he would like just with his just attitude, and he would let you improvise as much as you wanted. The bigger picture was definitely always George and the zombies and what he decided was really humane and ethical as opposed to not, and sometimes it was the humans who were not.

How collegial the set was in general? Were you hanging out at all with the zombies?

The zombies were made up separately, and we didn’t have much interaction with them. Most of them were working for a dollar a day, and they were so happy to be zombies, and they would often keep their makeup on — they were engaged completely. But we would shoot at night, and then at six in the morning, the mall would be turned back over to the owners of the mall and the Muzak would come on. And that’s when we would wrap. And Pittsburgh was icy and cold, so many people would use the mall to exercise. I remember a time the Muzak came on, and I see this group of people just walking in the mall, and I remember turning to them and saying, “no, we’ve wrapped. You can go home now,” thinking that they were zombies. They weren’t made up, but the way they were moving through the mall was exactly what George was depicting.

It feels unimaginable now to have the freedoms that it seems like you did in this mall. Were there any restrictions that you remember facing as you ran through these department stores?

We had complete free range. The guys that were running through Penneys with the guns and the cash — well fake cash, of course — it was just open-door. And then George brought in the motorcycle gang. They were really a motorcycle gang, and they had no idea, or any constraints about making films. I think they ended up having to repave the floor of the mall after the film because the motorcycles just destroyed it. And then there were certain effects that were not supposed to happen, like too many explosives when the door breaks. But nobody got killed.

Dawn of the Dead/ Katherine Kolbert

Can you remember any particular shenanigans you guys might’ve gotten into in that mall?

I don’t remember that we did anything unusual, but Scott invented that free fall down the escalator. That wasn’t scripted. George thought that was a great idea. And the ice skating rink was totally improvised because like a lot of actors did, I had put on my resume “special activities” and things that you can do, and I think I put down ice skating — because I did it when I was five years old. So I was sitting there and it was like 3:00 a.m. and George ran out of shots, and he came over to me and said, “it would be great to bring the crew down there and film you just skating.” And I remember running down to the skating rink, and to the guy who was managing, I said, “You’ve got to talk me around the rink because I can’t remember how to ice skate anymore.” So the whole time I was going, “Stand up straight!” But it worked, I didn’t fall. And then George said, “Yeah, far out.” That would be George’s answer to everything. “Yeah, far out, man. Let’s try it.”

Do you have any other specific memories of moments during production?

I remember we took a break over a month when Christmas was happening in the mall because they had to put all the decorations up so we couldn’t film then. So I went back to my acting instructor then, Mira Rostova, who came from the Moscow art theaters, this little bird of a woman. And we were all in a room, and each one of us would bring that script that we were working on. I brought in the script pages where I’m confronting being left with the Hare Krishna zombie, and everybody’s trying to keep a straight face while Mira was like trying to understand, “what is zombie?” But honest to God, she gave me line readings that would’ve been equivalent to what she would do if I were an actor playing Chekhov.

I understand there was a much more pessimistic ending George originally wrote.

We shot it! I prepared all day for it. George was going to kill us off — Peter was going to put a gun to his head, and I was going to put my head through the blades of the helicopter. We had already cast the head for that effect, so I think Savini used in another shop, because he wouldn’t want to waste that effect. But then the decision was that this was too dark an ending and that somebody had to survive. Whether or not anybody believes that we survived if I was driving a helicopter or not is another story.

Dawn of the Dead/ Katherine Kolbert

Was there a moment, whether it was during filming or after it was done, when you identified that you were capturing lightning in a bottle with this movie?

We thought it was something special. I think George thought so too, but he wasn’t sure. And at the beginning, the reviews were not good. And then it was Roger Ebert, and I can’t remember who else became champions of the film. But Scott, Ken, David and I were in Los Angeles at the time, looking at agents and having meetings and doing that, and none of them would look at the film! They would just say, “Oh, no, it’s a violent zombie film.” It was not taken seriously, and even though we were the leads, they were not giving us any benefit from it. So it took a while. Then of course, the popularity started to rise, and then the box office surprised everybody.

How much did Romero’s approach to this material shape any of your later documentary work?

I went from that to directing actors in theater and I think what I learned from George wasn’t so much his horror vision, but a respect and a generosity to actors, giving them the space. And also working later on as I did with documentaries, the relationship I have with the crew, what that means for them to work and what it means as they support me. The one thing that George had for everybody was a kindness and a respect. No matter how horrible the story was, he did that — and that’s why actors would return.

Given the direction that your career went after acting, has it been difficult or easy to embrace the fandom of this film?

It’s very compartmentalized. I mean, I’ve been directing documentaries for like 35 years now, and they’ve been in major film festivals all over the world. But my obituary’s still going to start with the line, “she starred in ‘Dawn of the Dead’.” And you know what? It’s okay. Because both things have worked out for me.